|

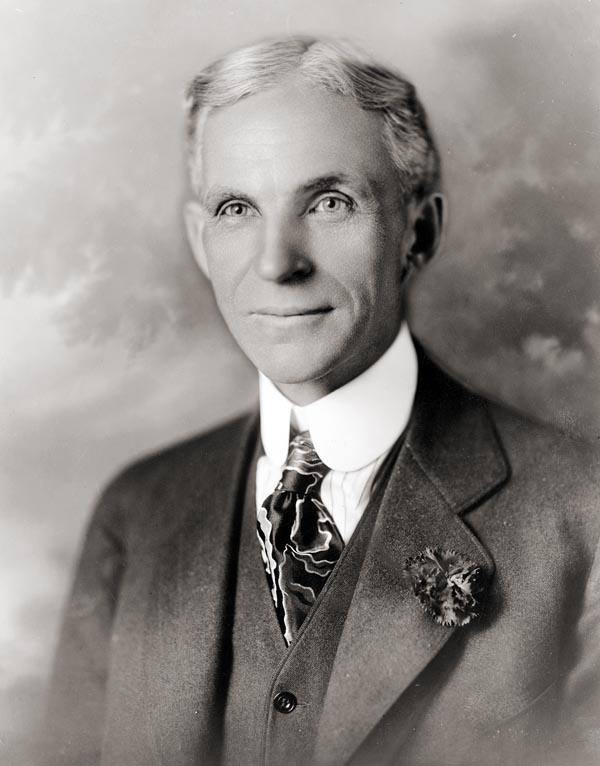

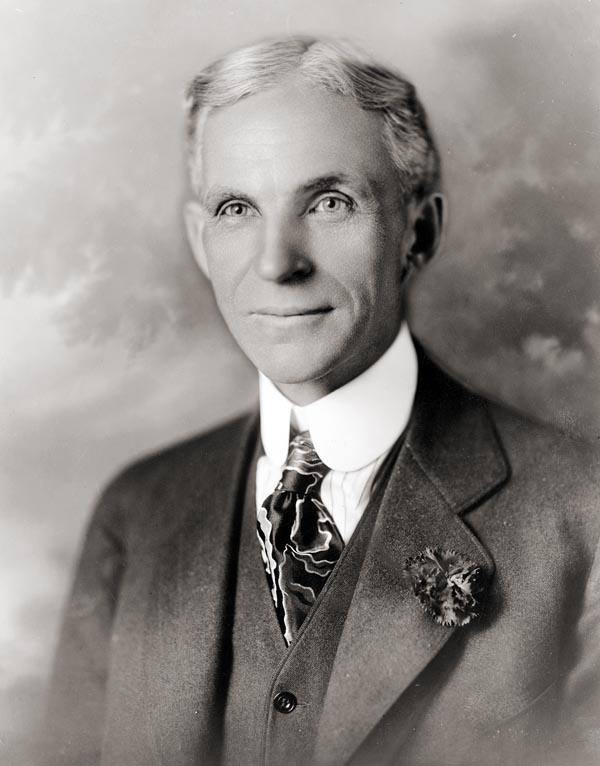

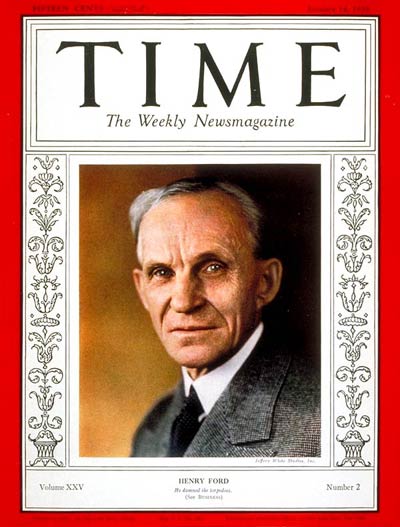

Henry Ford |

Henry Ford,

c. 1919 |

|

Born |

July 30, 1863

(1863-07-30)

Greenfield Township, Michigan, U.S. |

|

Died |

April 7, 1947

(1947-04-07)

(aged 83)

Fair Lane, Dearborn, Michigan, U.S. |

|

Occupation |

Business,

Engineering |

|

Net worth |

$188.1 billion, based on

information from Forbes, February 2008. |

|

Religion |

Protestant Episcopal |

|

Spouse |

Clara Jane Bryant |

|

Children |

Edsel Ford |

|

Parents |

William Ford and Mary Ford |

|

Signature |

|

Related Article:

Henry Ford -

This is Your Life

He was known worldwide especially in the 1920s

as a promoter of pacifism and as a publisher of

antisemitic texts such as the book The

International Jew.

Early years

Ford was born July 30, 1863, on a farm in Greenfield Township (near Detroit,

Michigan). His father, William Ford (1826?1905), was born in County Cork,

Ireland, of a family originally from western England, who were among

migrants to Ireland as the English created plantations. His mother, Mary

Litogot Ford (1839?1876), was born in Michigan; she was the youngest child

of Belgian immigrants; her parents died when Mary was a child and she was

adopted by neighbors, the O'Herns. Henry Ford's siblings include Margaret

Ford (1867?1938); Jane Ford (c. 1868?1945); William Ford (1871?1917) and

Robert Ford (1873?1934).

His father gave him a pocket watch in his early teens. At 15, Ford

dismantled and reassembled the timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of

times, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. At twenty, Ford walked

four miles to their Episcopal church every Sunday. His father gave him a pocket watch in his early teens. At 15, Ford

dismantled and reassembled the timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of

times, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. At twenty, Ford walked

four miles to their Episcopal church every Sunday.

Ford was devastated when his mother died in 1876. His father expected him to

eventually take over the family farm, but he despised farm work. He later

wrote, "I never had any particular love for the farm?it was the mother on

the farm I loved."

In 1879, he left home to work as an apprentice machinist in the city of

Detroit, first with James F. Flower & Bros., and later with the Detroit Dry

Dock Co. In 1882, he returned to Dearborn to work on the family farm, where

he became adept at operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine. He was

later hired by Westinghouse company to service their steam engines. During

this period Ford also studied bookkeeping at Goldsmith, Bryant & Stratton

Business College in Detroit.

Marriage and Family

Ford married Clara Ala Bryant (1866?1950) in 1888 and supported himself by

farming and running a sawmill. They had a single child: Edsel Ford

(1893?1943).

Career

In

1891, Ford became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating

Company. After his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had

enough time and money to devote attention to his personal

experiments on gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in

1896 with the completion of a self-propelled vehicle which he

named the Ford Quadricycle. He test-drove it on June 4. After

various test-drives, Ford brainstormed ways to improve the

Quadricycle. In

1891, Ford became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating

Company. After his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had

enough time and money to devote attention to his personal

experiments on gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in

1896 with the completion of a self-propelled vehicle which he

named the Ford Quadricycle. He test-drove it on June 4. After

various test-drives, Ford brainstormed ways to improve the

Quadricycle.

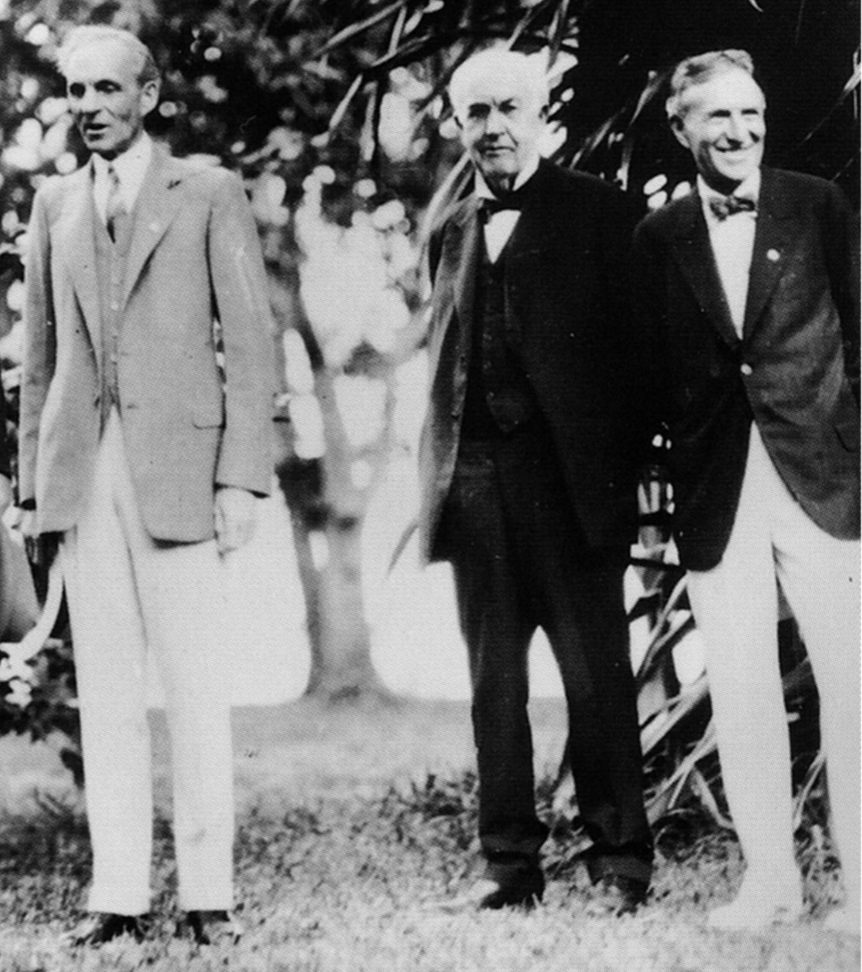

Also in 1896, Ford attended a meeting of Edison executives,

where he was introduced to Thomas Edison. Edison approved of

Ford's automobile experimentation; encouraged by him, Ford

designed and built a second vehicle, completing it in 1898.

Backed by the capital of Detroit lumber baron William H. Murphy,

Ford resigned from Edison and founded the Detroit Automobile

Company on August 5, 1899. However, the automobiles produced

were of a lower quality and higher price than Ford liked.

Ultimately, the company was not successful and was dissolved in

January 1901.

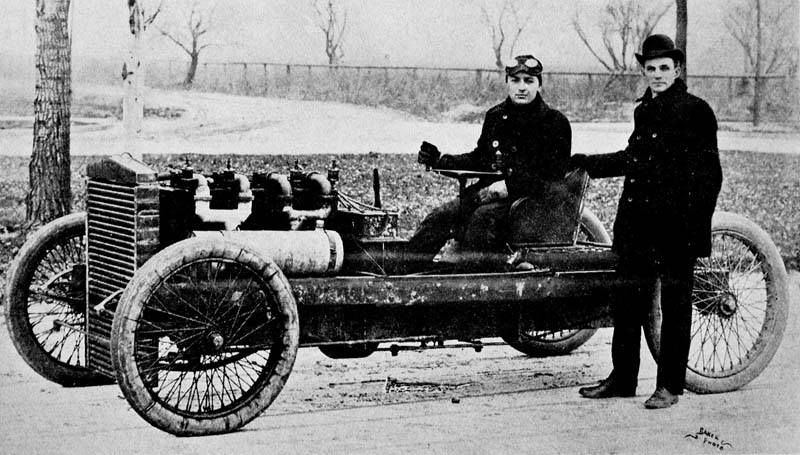

With the help of C. Harold Wills, Ford designed, built, and

successfully raced a 26-horsepower automobile in October 1901.

With this success, Murphy and other stockholders in the Detroit

Automobile Company formed the Henry Ford Company on November 30,

1901, with Ford as chief engineer. However, Murphy brought in

Henry M. Leland as a consultant and, as a result, Ford left the

company bearing his name in 1902. With Ford gone, Murphy renamed

the company the Cadillac Automobile Company.

Teaming up with former racing cyclist Tom Cooper, Ford also

produced the 80+ horsepower racer "999" which Barney Oldfield

was to drive to victory in a race in October 1902. Ford received

the backing of an old acquaintance, Alexander Y. Malcomson, a

Detroit-area coal dealer. They formed a partnership, "Ford & Malcomson, Ltd." to manufacture automobiles. Ford went to work

designing an inexpensive automobile, and the duo leased a

factory and contracted with a machine shop owned by John and

Horace E. Dodge to supply over $160,000 in parts. Sales were

slow, and a crisis arose when the Dodge brothers demanded

payment for their first shipment.

A

Tinkerer In An Emerging Industry

By rights, Henry Ford

probably should have been a farmer. He was born in 1863 in

Dearborn, Michigan, on the farm operated by his father, an

Irishman, and his mother, who was from Dutch stock. Even as a

boy, young Henry had an aptitude for inventing and used it to

make machines that reduced the drudgery of farm chores. At the

age of thirteen, he saw a coal-fired steam engine lumbering

along a long rural road, a sight that galvanized his fascination

with machines. At sixteen, against the wishes of his father, he

left the farm for Detroit, where he found work as a mechanic's

apprentice. Over the next dozen years he advanced steadily, and

became chief engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company.

At twenty-four, Ford

married Clara Bryant, a friend of his sister's; he called her

"The Believer," because she encouraged his plans to build a

horseless carriage from their earliest days together. For as

Henry Ford oversaw the steam engines and turbines that produced

electricity for Detroit Edison, inventors in the U.S. and Europe

were adapting such engines to small passenger vehicles. On

January 29, 1886, Karl Benz received a patent for a crude

gas-fueled car, which he demonstrated later that year on the

streets of Mannhelm, Germany. And in 1893, Charles and Frank

Duryea, of Springfield, Massachusetts, built the first

gas-operated vehicle in the U.S.

In the 1890s, any mechanic with tools, a workbench, and a

healthy imagination was a potential titan in the infant

industry. Even while continuing his career at Edison, Ford

devoted himself to making a working automobile. In 1891, he

presented Clara with a design for an internal combustion engine,

drawn on the back of a piece of sheet music. Bringing the design

to reality was another matter, but on Christmas Eve 1893 he made

a successful test of one of his engines, in the kitchen sink.

The engine was merely the heart of the new machine that Ford

hoped to build. On weekends and most nights, he could be found

in a shed in the back of the family home, building the rest of

the car. So great was his obsession that the neighbors called

him Crazy Henry. However, at 2:00 A.M. on June 4, 1896, Crazy

Henry punched a large hole in the wall of his shed, and emerged

at the wheel of an automobile -- his automobile. In the weeks

that followed, Ford was often seen driving around the streets of

Detroit.

Later that year, Ford attended a national meeting of Edison

employees. Thomas A. Edison had been Ford's idol for years. But

at the meeting, it was Edison who asked to meet the young

inventor, after word got around that the obscure engineer from

Detroit had actually built an automobile. "Young man, you have

the right idea," Edison said. "Keep right at it". Ironically, he

was adamant that Ford not waste his time trying to make a car

run viably on electricity.

Back in Detroit, Ford showed that he was no mere hobbyist: he

sold his prototype for $200. For three years, he watched the new

field of automaking develop, and he progressed along with it. In

1899, thirty American manufacturers -- most of them based in New

England -- produced about 2,500 cars. Still, most Americans in

the market for automobiles became accustomed to buying imported

ones. In 1898, though, the domestic bicycle industry faced an

unusual slump and many manufacturers decided to turn to

automaking to keep the factories busy.

Offered a senior position and part ownership of a new company,

the Detroit Automobile Co., Ford, thirty-six years old, quit the

Edison Illuminating Company. Across town, the firm that would

become Oldsmobile was launched at the same time. The Detroit

Automobile Co. failed, without producing any cars, and Henry

Ford was ousted by angry investors. (The firm survived, emerging

from reorganization as the Cadillac Motor Car Company.)

Building a Car for the Great

Multitude

Ford continued to

pursue his dream. Early automobile promotion took place largely

on the racetrack, where manufacturers sought to prove

roadworthiness by putting their cars on public view and pressing

them to their very limits. In 1901, Henry Ford poured his

expertise into a pair of big race cars, one of which he entered

in a ten-mile match race against a car built by Alexander

Winton, a leading automaker from Ohio. The race took place in

Grosse Pointe, Michigan, and Ford's car won. Because of the

victory, the coal merchant Alexander Malcomson agreed to back

Ford in a new business venture. In 1903, they formed the Ford

Motor Company, in association with about a dozen other

investors. Capitalized at $100,000, the company actually started

with cash on hand of about $28,000. Some investors contributed

other types of capital; for example, the Dodge brothers, John

and Horace, agreed to supply engines.

The company purchased most of the major components for its new

models, a common practice of the day. Teams of mechanics built

cars individually at workstations, gathering parts as needed

until a car was complete. In 1903, Ford's 125 workers made 1,700

cars in three different models. The cars were comparatively

expensive, and their high profit-margins pleased the

stockholders. Malcomson decided to start yet another automobile

company. But when it failed, he was forced to sell his other

assets, including his shares in Ford. Henry Ford bought enough

of them to assume a majority position. The most important

stockholder outside of the Ford family was James Couzens,

Malcomson's former clerk; as General Manager, then vice

president and secretary-treasurer at the Ford Motor Company, he

was effectively second-in-command throughout many of the Model T

years.

The direction of the company toward even pricier models had

bothered Henry Ford. He used his new power to curtail their

production, a move that coincided with the Panic of 1907. This

case of accidental good timing probably saved the company. Ford,

insisting that high prices ultimately slowed market expansion,

had decided in 1906 to introduce a new, cheaper model with a

lower profit margin: the Model N. Many of his backers disagreed.

While the N was only a tepid success, Ford nonetheless pressed

forward with the design of the car he really wanted to build.

The car that would be the Model T.

"I

will build a motorcar for the great multitude," he

proclaimed. Such a notion was revolutionary. Until then the

automobile had been a status symbol painstakingly manufactured

by craftsmen. But Ford set out to make the car a commodity.

"Just like one pin is like another pin when it comes from the

pin factory, or one match is like another match when it comes

from the match factory," he said. This was but the first of

several counterintuitive moves that Ford made throughout his

unpredictable career. Prickly, brilliant, willfully eccentric,

he relied more on instinct than business plans. As the eminent

economist John Kenneth Galbraith later said: "If there is any

certainty as to what a businessman is, he is assuredly the

things Ford was not." "I

will build a motorcar for the great multitude," he

proclaimed. Such a notion was revolutionary. Until then the

automobile had been a status symbol painstakingly manufactured

by craftsmen. But Ford set out to make the car a commodity.

"Just like one pin is like another pin when it comes from the

pin factory, or one match is like another match when it comes

from the match factory," he said. This was but the first of

several counterintuitive moves that Ford made throughout his

unpredictable career. Prickly, brilliant, willfully eccentric,

he relied more on instinct than business plans. As the eminent

economist John Kenneth Galbraith later said: "If there is any

certainty as to what a businessman is, he is assuredly the

things Ford was not."

In the winter of 1906, Ford had secretly partitioned a twelve-by

fifteen-foot room in his plant, on Piquette Avenue in Detroit.

With a few colleagues, he devoted two years to the design and

planning of the Model T. Early on, they made an extensive study

of materials, the most valuable aspect of which began in an

offhand way. During a car race in Florida, Ford examined the

wreckage of a French car and noticed that many of its parts were

of lighter-than-ordinary steel. The team on Piquette Avenue

ascertained that the French steel was a vanadium alloy, but that

no one in America knew how to make it. The finest steel alloys

then used in American automaking provided 60,000 pounds of

tensile strength. Ford learned that vanadium steel, which was

much lighter, provided 170,000 pounds of tensile strength. As

part of the pre-production for the new model, Ford imported a

metallurgist and bankrolled a steel mill. As a result, the only

cars in the world to utilize vanadium steel in the next five

years would be French luxury cars and the Ford Model T. A Model

T might break down every so often, but it would not break.

The car that finally emerged from Ford's secret design section

at the factory would change America forever. For $825, a Model T

customer could take home a car that was light, at about 1,200

pounds; relatively powerful, with a four-cylinder, twenty

horsepower engine, and fairly easy to drive, with a two-speed,

foot-controlled "planetary" transmission. Simple, sturdy, and

versatile, the little car would excite the public imagination.

It certainly fired up its inventor: when Henry Ford brought the

prototype out of the factory for its first test drive, he was

too excited to drive. An assistant had to take the wheel.

"Well, I guess we've got started," Ford observed at the time.

The car went to the first customers on October 1, 1908. In its

first year, over ten thousand were sold, a new record for an

automobile model. Sales of the "Tin Lizzie," or "flivver," as

the T was known, were boosted by promotional activities ranging

from a black-tie "Ford Clinic" in New York, where a team of

mechanics showcased the car, to Model T rodeos out west, in

which cowboys riding in Fords tried to rope calves. In 1909,

mining magnate Robert Guggenheim sponsored an auto race from New

York to Seattle in which the only survivors were two Model T

Fords. "I believe Mr. Ford has the solution of the popular

automobile," Guggenheim concluded.

In the early years, Model Ts were produced at Piquette Avenue in

much the same way that all other cars were built. Growing demand

for the new Ford overwhelmed the old method, though. Ford

realized that he not only had to build a new factory, but a new

system within that factory.

Throughout his tenure as the head of the company, Henry Ford

believed in maintaining enormous cash reserves, a policy that

allowed him to plan a new facility for production of the Model T

without interference or outside pressure. The new Highland Park

factory, which opened in 1910, was designed by the nation's

leading industrial architect, Albert Kahn. It was unparalleled

in scale, sprawling over sixty-two acres. John D. Rockefeller,

whose Standard Oil refineries had always represented

state-of-the-art design, called Highland Park "the industrial

miracle of the age."

In

its first few years, the four-story Highland Park factory was

organized from top to bottom. Assembly wound downward, from the

fourth floor, where body panels were hammered out, to the third

floor, where workers placed tires on wheels and painted auto

bodies. After assembly was completed on the second floor, new

automobiles descended a final ramp past the first-floor offices.

Production increased by approximately 100 percent in each of the

first three years, from 19,000 in 1910, to 34,500 in 1911, to a

staggering 78,440 in 1912. It was still only a start. In

its first few years, the four-story Highland Park factory was

organized from top to bottom. Assembly wound downward, from the

fourth floor, where body panels were hammered out, to the third

floor, where workers placed tires on wheels and painted auto

bodies. After assembly was completed on the second floor, new

automobiles descended a final ramp past the first-floor offices.

Production increased by approximately 100 percent in each of the

first three years, from 19,000 in 1910, to 34,500 in 1911, to a

staggering 78,440 in 1912. It was still only a start.

"I'm going to democratize the automobile," Henry Ford had said

in 1909. "When I'm through, everybody will be able to afford

one, and about everybody will have one." The means to this end

was a continuous reduction in price. When it sold for $575 in

1912, the Model T for the first time cost less than the

prevailing average annual wage in the United States. Ignoring

conventional wisdom, Ford continually sacrificed profit margins

to increase sales. In fact, profits per car did fall as he

slashed prices from $220 in 1909 to $99 in 1914. But sales

exploded, rising to 248,000 in 1913. Moreover, Ford demonstrated

that a strategic, systematic lowering of prices could boost

profits, as net income rose from $3 million in 1909 to $25

million in 1914. As Ford's U.S. market share rose from a

respectable 9.4 percent in 1908 to a formidable 48 percent in

1914, the Model T dominated the world's leading market.

At Highland Park, Ford began to implement factory automation in

1910. But experimentation would continue every single day for

the next seventeen years, under one of Ford's maxims:

"Everything can always be done better than it is being done."

Ford and his efficiency experts examined every aspect of

assembly and tested new methods to increase productivity. The

boss himself claimed to have found the inspiration for the

greatest breakthrough of all, the moving assembly line, on a

trip to Chicago: "The idea came in a general way from the

overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef,"

Ford said. At the stockyards, butchers removed certain cuts as

each carcass passed by, until nothing was left. Ford reversed

the process. His use of the moving assembly line was complicated

by the fact that parts, often made on sub-assembly lines, had to

feed smoothly into the process. Timing was crucial: a clog along

a smaller line would slow work farther along. The first moving

line was tested with assembly of the flywheel magneto, showing a

saving of six minutes, fifty seconds over the old method. As

similar lines were implemented throughout Highland Park, the

assembly time for a Model T chassis dropped from twelve hours,

thirty minutes to five hours, fifty minutes.

The

pace only accelerated, as Ford's production engineers

experimented with work slides, rollways, conveyor belts, and

hundreds of other ideas. The first and most effective assembly

line in the automobile industry was continually upgraded. Those

most affected were, of course, the workers. As early as January

1914, Ford developed an "endless chain-driven" conveyor to move

the chassis from one workstation to another; workers remained

stationary. Three months later, the company created a "man high"

line -- with all the parts and belts at waist level, so that

workers could repeat their assigned tasks without having to move

their feet. The

pace only accelerated, as Ford's production engineers

experimented with work slides, rollways, conveyor belts, and

hundreds of other ideas. The first and most effective assembly

line in the automobile industry was continually upgraded. Those

most affected were, of course, the workers. As early as January

1914, Ford developed an "endless chain-driven" conveyor to move

the chassis from one workstation to another; workers remained

stationary. Three months later, the company created a "man high"

line -- with all the parts and belts at waist level, so that

workers could repeat their assigned tasks without having to move

their feet.

In 1914, 13,000 workers at Ford made 260,720 cars. By

comparison, in the rest of the industry, it took 66,350 workers

to make 286,770. Critics charged that the division of the

assembly process into mindless, repetitive tasks turned most of

Ford's employees into unthinking automatons, and that

manipulation of the pace of the line was tantamount to slave

driving by remote control. The men who made cars no longer had

to be mechanically inclined, as in the earlier days; they were

just day laborers. Ford chose to see the bigger picture of the

employment he offered. "I have heard it said, in fact, I believe

it's quite a current thought, that we have taken skill out of

work," he said. "We have not. We have put a higher skill into

planning, management, and tool building, and the results of that

skill are enjoyed by the man who is not skilled."

But the unskilled workers, many of them foreign born, didn't

enjoy their work, earning a mediocre $2.38 for a nine-hour day.

Indeed, the simplification of the jobs created a treacherous

backlash: high turnover. Over the course of 1913, the company

had to hire 963 workers for every 100 it needed to maintain on

the payroll. To keep a workforce of 13,600 employees in the

factory, Ford continually spent money on short-term training.

Even though the company introduced a program of bonuses and

generous benefits, including a medical clinic, athletic fields,

and playgrounds for the families of workers, the problem

persisted. The rest of the industry reluctantly accepted high

turnover as part of the assembly-line system and passed the

increasing labor costs into the prices of their cars. Henry

Ford, however, did not want anything in the price of a Model T

except good value. His solution was a bold stroke that

reverberated through the entire nation.

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford announced a new minimum wage of

five dollars per eight-hour day, in addition to a profit-sharing

plan. It was the talk of towns across the country; Ford was

hailed as the friend of the worker, as an outright socialist, or

as a madman bent on bankrupting his company. Many businessmen --

including most of the remaining stockholders in the Ford Motor

Company -- regarded his solution as reckless. But he shrugged

off all the criticism: "Well, you know when you pay men well you

can talk to them," he said. Recognizing the human element in

mass production, Ford knew that retaining more employees would

lower costs, and that a happier work force would inevitably lead

to greater productivity. The numbers bore him out. Between 1914

and 1916, the company's profits doubled from $30 million to $60

million. "The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour

day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made," he

later said.

There were other ramifications, as well. A budding effort to

unionize the Ford factory dissolved in the face of the

Five-Dollar Day. Most cunning of all, Ford's new wage scale

turned autoworkers into auto customers. The purchases they made

returned at least some of those five dollars to Henry Ford, and

helped raise production, which invariably helped to lower

per-car costs.

The central role that the Model T had come to play in America's

cultural, social and economic life elevated Henry Ford into a

full-fledged folk hero. But Ford wasn't satisfied. Fancying

himself a political pundit and all-around sage, he allowed

himself to be drawn into national and even world affairs. Before

the United States entered World War I, he despaired with many

others over the horrors of the fighting; late in 1915, he

chartered a "Peace Ship" and sailed with a private delegation of

radicals for France in a native attempt to end the war. In 1918,

he lost a campaign for a U.S. Senate seat. The following year,

he purchased a newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, which was to

become the vehicle for his notorious anti-Semitism. The

newspaper railed against the International Jew, and reported

scurrilous conspiracy theories such as The Protocols of the

Elders of Zion.

In

1915, James Couzens resigned from the Ford Motor Company,

recognizing that it Henry's company, and that no one else's

opinion would ever matter as much. In 1916, Ford antagonized the

other shareholders by declaring a paltry dividend, even in the

face of record profits. In response, the shareholders sued, and

in 1919 the Michigan Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling

that it was unreasonable to withhold fair dividends under the

circumstances. The Ford Motor Company was forced to distribute

$19 million in dividend payments. In his own response to the

escalating feud, Henry threatened publicly to leave the company

and form a new one. He even made plans and discussed the next

car he would produce. In

1915, James Couzens resigned from the Ford Motor Company,

recognizing that it Henry's company, and that no one else's

opinion would ever matter as much. In 1916, Ford antagonized the

other shareholders by declaring a paltry dividend, even in the

face of record profits. In response, the shareholders sued, and

in 1919 the Michigan Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling

that it was unreasonable to withhold fair dividends under the

circumstances. The Ford Motor Company was forced to distribute

$19 million in dividend payments. In his own response to the

escalating feud, Henry threatened publicly to leave the company

and form a new one. He even made plans and discussed the next

car he would produce.

Fearing that the worth of Ford stock would plummet, the minority

shareholders suddenly became eager to sell; agents working

surreptitiously for Henry Ford quietly bought up lot after lot

of shares. The sellers did not receive all that the shares were

worth, because of the rumors, but they each emerged with a

fortune. James Couzens, the most wily of the lot, received the

highest price per share, and turned to a career in the U.S.

Senate (he won his race, unlike the old boss) with $30 million

in the bank. Ford gained complete control of the company at a

cost of $125 million -- $106 million of the stock, plus $19

million for the court-ordered dividend -- a fantastic outlay

that he financed with a $75 million loan from two eastern banks.

On July 11, 1919, when he signed the last stock transfer

agreement, the fifty-five-year-old mogul was so enthused that he

danced a jig. The stock was divided up and placed in the names

of Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford.

In 1921, the Model T Ford held 60 percent of the new-car market.

Plants around the world turned out flivvers as though they were

subway tokens, and Henry Ford's only problem, as he often stated

it, was figuring out how to make enough of them. As a concession

to diversification, he purchased the Lincoln Motor Car Company

in 1921. Company plans seemed to be in place for a long,

predictable future and Ford was free to embark on a great new

project: the design and construction of the world's largest and

most efficient automobile factory at River Rouge, near Detroit.

Arrayed over 2,000 acres, it would include 90 miles of railroad

track and enough space for 75,000 employees to produce finished

cars from raw material in the span of just forty-one hours.

River Rouge had its own power plant, iron forges, and

fabricating facilities. No detail was overlooked: wastepaper

would be recycled into cardboard at the factory's own paper

mill. River Rouge was built to produce Model T Fords for decades

to come, by the time it was capable of full production later in

the decade, a factory a tenth its size could have handled the

demand for Model Ts.

Ford Motor Company

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors

and convinced the Dodge Brothers to accept a portion of the new

company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the

Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, with $28,000 capital.

The original investors included Ford and Malcomson, the Dodge

brothers, Malcomson's uncle

John S. Gray,

James Couzens, and two of Malcomson's lawyers, John W.

Anderson and

Horace Rackham. In a newly designed car, Ford gave an

exhibition on the ice of

Lake St. Clair, driving 1 mile (1.6 km) in 39.4 seconds,

setting a new

land speed record at 91.3 miles per hour (147.0 km/h).

Convinced by this success, the race driver

Barney Oldfield, who named this new Ford model "999" in

honor of a racing locomotive of the day, took the car around the

country, making the Ford brand known throughout the United

States. Ford also was one of the early backers of the

Indianapolis 500. In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors

and convinced the Dodge Brothers to accept a portion of the new

company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the

Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, with $28,000 capital.

The original investors included Ford and Malcomson, the Dodge

brothers, Malcomson's uncle

John S. Gray,

James Couzens, and two of Malcomson's lawyers, John W.

Anderson and

Horace Rackham. In a newly designed car, Ford gave an

exhibition on the ice of

Lake St. Clair, driving 1 mile (1.6 km) in 39.4 seconds,

setting a new

land speed record at 91.3 miles per hour (147.0 km/h).

Convinced by this success, the race driver

Barney Oldfield, who named this new Ford model "999" in

honor of a racing locomotive of the day, took the car around the

country, making the Ford brand known throughout the United

States. Ford also was one of the early backers of the

Indianapolis 500.

Model T

The

Model T was introduced on October 1, 1908. It had the

steering wheel on the left, which every other company soon

copied. The entire engine and transmission were enclosed; the

four cylinders were cast in a solid block; the suspension used

two semi-elliptic springs. The car was very simple to drive, and

easy and cheap to repair. It was so cheap at $825 in 1908

($21,340 today) (the price fell every year) that by the 1920s, a

majority of American drivers had learned to drive on the Model

T.

Ford created a massive publicity machine in Detroit to ensure

every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product.

Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in

virtually every city in North America. As independent dealers,

the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but

the very concept of automobiling; local motor clubs sprang up to

help new drivers and to encourage exploring the countryside.

Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked on the

vehicle as a commercial device to help their business. Sales

skyrocketed?several years posted 100% gains on the previous

year. Always on the hunt for more efficiency and lower costs, in

1913 Ford introduced the moving assembly belts into his plants,

which enabled an enormous increase in production. Although Ford

is often credited with the idea, contemporary sources indicate

that the concept and its development came from employees

Clarence Avery,

Peter E. Martin,

Charles E. Sorensen, and

C. Harold Wills.

Sales passed 250,000 in 1914. By 1916, as the price dropped

to $360 for the basic touring car, sales reached 472,000. (Using

the consumer price index, this price was equivalent to $7,020 in

2008 dollars.) Sales passed 250,000 in 1914. By 1916, as the price dropped

to $360 for the basic touring car, sales reached 472,000. (Using

the consumer price index, this price was equivalent to $7,020 in

2008 dollars.)

By 1918, half of all cars in America were Model T's. However,

it was a monolithic black; as Ford wrote in his autobiography,

"Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so

long as it is black". Until the development of the assembly

line, which mandated black because of its quicker drying time,

Model T's were available in other colors, including red. The

design was fervently promoted and defended by Ford, and

production continued as late as 1927; the final total production

was 15,007,034. This record stood for the next 45 years. This

record was achieved in just 19 years from the introduction of

the first

Model T (1908).

President

Woodrow Wilson asked Ford to run as a Democrat for the

United States Senate from Michigan in 1918. Although the

nation was at war, Ford ran as a peace candidate and a strong

supporter of the proposed

League of Nations.

Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over

to his son

Edsel Ford in December 1918. Henry, however, retained final

decision authority and sometimes reversed his son. Henry started

another company, Henry Ford and Son, and made a show of taking

himself and his best employees to the new company; the goal was

to scare the remaining holdout stockholders of the Ford Motor

Company to sell their stakes to him before they lost most of

their value. (He was determined to have full control over

strategic decisions.) The ruse worked, and Henry and Edsel

purchased all remaining stock from the other investors, thus

giving the family sole ownership of the company. Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over

to his son

Edsel Ford in December 1918. Henry, however, retained final

decision authority and sometimes reversed his son. Henry started

another company, Henry Ford and Son, and made a show of taking

himself and his best employees to the new company; the goal was

to scare the remaining holdout stockholders of the Ford Motor

Company to sell their stakes to him before they lost most of

their value. (He was determined to have full control over

strategic decisions.) The ruse worked, and Henry and Edsel

purchased all remaining stock from the other investors, thus

giving the family sole ownership of the company.

By the mid-1920s, sales of the Model T began to decline due

to rising competition. Other auto makers offered payment plans

through which consumers could buy their cars, which usually

included more modern mechanical features and styling not

available with the Model T. Despite urgings from Edsel, Henry

steadfastly refused to incorporate new features into the Model T

or to form a customer credit plan.

Model A and Ford's later career

By 1926, flagging sales of the Model T finally convinced

Henry to make a new model. He pursued the project with a great

deal of technical expertise in design of the engine, chassis,

and other mechanical necessities, while leaving the body design

to his son. Edsel also managed to prevail over his father's

initial objections in the inclusion of a sliding-shift

transmission.

The result was the successful

Ford Model A, introduced in December 1927 and produced

through 1931, with a total output of more than 4 million.

Subsequently, the Ford company adopted an annual model change

system similar to that recently pioneered by its competitor

General Motors (and still in use by automakers today). Not until

the 1930s did Ford overcome his objection to finance companies,

and the Ford-owned

Universal Credit Corporation became a major car-financing

operation.

Ford did not believe in accountants; he amassed one of the

world's largest fortunes without ever having his company

audited under his administration.

Labor philosophy

The

five-dollar workday

Ford was a pioneer of "welfare

capitalism", designed to improve the lot of his workers and

especially to reduce the heavy

turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year

to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best

workers. Ford was a pioneer of "welfare

capitalism", designed to improve the lot of his workers and

especially to reduce the heavy

turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year

to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best

workers.

Ford astonished the world in 1914 by offering a $5 per day

wage ($120 today), which more than doubled the rate of most of

his workers. A Cleveland, Ohio newspaper editorialized that the

announcement "shot like a blinding rocket through the dark

clouds of the present industrial depression." The move proved

extremely profitable; instead of constant turnover of employees,

the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing their

human capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering

training costs. Ford announced his $5-per-day program on January

5, 1914, raising the minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for

qualifying workers. It also set a new, reduced workweek,

although the details vary in different accounts. Ford and

Crowther in 1922 described it as six 8-hour days, giving a

48-hour week, while in 1926 they described it as five 8-hour

days, giving a 40-hour week. (Apparently the program started

with Saturdays as workdays and sometime later it was changed to

a day off.)

Detroit was already a high-wage city, but competitors were

forced to raise wages or lose their best workers. Ford's policy

proved, however, that paying people more would enable Ford

workers to afford the cars they were producing and be good for

the economy. Ford explained the policy as profit-sharing rather

than wages. It may have been

Couzens who convinced Ford to adopt the $5 day.

The profit-sharing was offered to employees who had worked at

the company for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted

their lives in a manner of which Ford's "Social Department"

approved. They frowned on heavy drinking, gambling, and what

might today be called "deadbeat

dads". The Social Department used 50 investigators, plus

support staff, to maintain employee standards; a large

percentage of workers were able to qualify for this

"profit-sharing."

Ford's incursion into his employees' private lives was highly

controversial, and he soon backed off from the most intrusive

aspects. By the time he wrote his 1922 memoir, he spoke of the

Social Department and of the private conditions for

profit-sharing in the past tense, and admitted that "paternalism

has no place in industry. Welfare work that consists in prying

into employees' private concerns is out of date. Men need

counsel and men need help, oftentimes special help; and all this

ought to be rendered for decency's sake. But the broad workable

plan of investment and participation will do more to solidify

industry and strengthen organization than will any social work

on the outside. Without changing the principle we have changed

the method of payment."

Labor unions

Ford was adamantly against

labor unions. He explained his views on unions in Chapter 18

of My Life and Work. He thought they were too heavily

influenced by some leaders who, despite their ostensible good

motives, would end up doing more harm than good for workers.

Most wanted

to restrict productivity as a means to foster employment, but

Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view,

productivity was necessary for any economic prosperity to exist. Ford was adamantly against

labor unions. He explained his views on unions in Chapter 18

of My Life and Work. He thought they were too heavily

influenced by some leaders who, despite their ostensible good

motives, would end up doing more harm than good for workers.

Most wanted

to restrict productivity as a means to foster employment, but

Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view,

productivity was necessary for any economic prosperity to exist.

He believed that productivity gains that obviated certain

jobs would nevertheless stimulate the larger economy and thus

grow new jobs elsewhere, whether within the same corporation or

in others. Ford also believed that union leaders (particularly

Leninist-leaning ones) had a perverse incentive to foment

perpetual socio-economic crisis as a way to maintain their own

power. Meanwhile, he believed that smart managers had an

incentive to do right by their workers, because doing so would

maximize their own profits. (Ford did acknowledge, however, that

many managers were basically too bad at managing to understand

this fact.) But Ford believed that eventually, if good managers

such as he could fend off the attacks of misguided people from

both left and right (i.e., both socialists and bad-manager

reactionaries), the good managers would create a socio-economic

system wherein neither bad management nor bad unions could find

enough support to continue existing.

To forestall union activity, Ford promoted

Harry Bennett, a former

Navy boxer, to head the Service Department. Bennett employed

various intimidation tactics to squash union organizing. The

most famous incident, in 1937, was a bloody brawl between

company security men and organizers that became known as

The Battle of the Overpass.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Edsel (who was president

of the company) thought Ford had to come to some sort of

collective bargaining agreement with the unions, because the

violence, work disruptions, and bitter stalemates could not go

on forever. But Henry (who still had the final veto in the

company on a de facto basis even if not an official one)

refused to cooperate. For several years, he kept Bennett in

charge of talking to the unions that were trying to organize the

Ford company. Sorensen's memoir makes clear that Henry's purpose

in putting Bennett in charge was to make sure no agreements were

ever reached.

The Ford company was the last Detroit automaker to recognize

the

United Auto Workers union (UAW). A sit-down strike by the

UAW union in April 1941 closed the

River Rouge Plant. Sorensen recounted that a distraught

Henry Ford was very close to following through with a threat to

break up the company rather than cooperate but that his wife

Clara told him she would leave him if he destroyed the family

business. She wanted to see their son and grandsons lead it into

the future. Henry complied with his wife's ultimatum. Overnight,

the Ford Motor Co. went from the most stubborn holdout among

automakers to the one with the most favorable UAW contract

terms. The contract was signed in June 1941.

Ford Airplane Company

Ford, like other automobile companies, entered the aviation

business during

World War I, building Liberty engines. After the war, it

returned to auto manufacturing until 1925, when Ford acquired

the

Stout Metal Airplane Company. Ford, like other automobile companies, entered the aviation

business during

World War I, building Liberty engines. After the war, it

returned to auto manufacturing until 1925, when Ford acquired

the

Stout Metal Airplane Company.

Ford's most successful aircraft was the

Ford 4AT Trimotor, often called the "Tin Goose" because of

its corrugated metal construction. It used a new alloy called

Alclad that combined the corrosion resistance of aluminum

with the strength of

duralumin. The plane was similar to

Fokker's V.VII-3m, and some say that Ford's engineers

surreptitiously measured the Fokker plane and then copied it.

The Trimotor first flew on June 11, 1926, and was the first

successful U.S. passenger airliner, accommodating about 12

passengers in a rather uncomfortable fashion. Several variants

were also used by the

U.S. Army. Ford has been honored by the

Smithsonian Institution for changing the aviation industry.

199 Trimotors were built before it was discontinued in 1933,

when the Ford Airplane Division shut down because of poor sales

during the

Great Depression.

Willow Run

President

Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to Detroit as the "Arsenal

of Democracy". The Ford Motor Company played a pivotal role

in the

Allied victory during World War I and

World War II. With Europe under siege, the Ford company's

genius turned to mass production for the war effort.

Specifically, Ford developed mass production for the

B-24 Liberator bomber, still the most-produced

Allied bomber in history. When the planes started being used

in the war zones, the balance of power shifted to the Allies.

Before Ford, and under optimal conditions, the aviation

industry could produce one Consolidated Aircraft B-24 Bomber a

day at an aircraft plant. Ford showed the world how to produce

one B-24 an hour at a peak of 600 per month in 24-hour shifts.

Ford's

Willow Run factory broke ground in April 1941. At the time,

it was the largest assembly plant in the world, with over

3,500,000 square feet (330,000 m).

Mass production of the B-24, led by Charles Sorensen and

later Mead Bricker, began by August 1943. Many pilots slept on

cots waiting for takeoff as the B-24s rolled off the assembly

line at Ford's Willow Run facility.

Peace and war

World War I

era World War I

era

Ford opposed war, which he thought was a terrible waste. Ford

became highly critical of those who he felt financed war, and he

tried to stop them. In 1915, the pacifist

Rosika Schwimmer gained favor with Ford, who agreed to fund

a peace ship to Europe, where World War I was raging. He and

about 170 other prominent peace leaders traveled there. Ford's

Episcopalian pastor, Reverend Samuel S. Marquis, accompanied him

on the mission. Marquis headed Ford's Sociology Department from

1913 to 1921. Ford talked to President Wilson about the mission

but had no government support. His group went to neutral Sweden

and the Netherlands to meet with peace activists. A target of

much ridicule, Ford left the ship as soon as it reached Sweden.

Ford plants in Britain produced tractors to increase the

British food supply, as well as trucks and aircraft engines.

When the U.S. entered the war in 1917 the company became a major

supplier of weapons, especially the Liberty engine for

airplanes, and anti-submarine boats.

In 1918, with the war on and the

League of Nations a growing issue in global politics,

President

Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, encouraged Ford to run for a

Michigan seat in the U.S. Senate. Wilson believed that Ford

could tip the scales in Congress in favor of Wilson's proposed

League. "You are the only man in Michigan who can be elected

and help bring about the peace you so desire," the president

wrote Ford. Ford wrote back: "If they want to elect me let them

do so, but I won't make a penny's investment." Ford did run,

however, and came within 4,500 votes of winning, out of more

than 400,000 cast statewide.

Mental collapse and World War II

Ford had long opposed war and continued to believe that

international business could generate the prosperity that would

head off wars; when World War II erupted in 1939 he said the

people of the world had been duped. Like many other businessmen

of the Great Depression era, he never liked or entirely trusted

the Franklin Roosevelt Administration. He was not, however,

active in

the isolationist movement of 1939?41, and he supported the

American war effort and realized the need to support Britain

with weapons to fight the Nazis. However, when

Rolls-Royce sought a US manufacturer as an alternative

source for the

Merlin engine (as fitted to the

Spitfire and

Hurricane), Ford first agreed to do so and then

reneged. He "lined up behind the war effort" when the U.S.

entered in late 1941, and the company became a major component

of the "Arsenal

of Democracy." Following a series of strokes in the late

1930s he became increasingly senile and was more of a

figurehead; other people made the decisions in his name. After

Edsel Ford's death, Henry Ford nominally resumed control of

the company in 1943, but his mental strength was fading fast. In

reality the company was controlled by a handful of senior

executives led by

Charles Sorensen and

Harry Bennett; Sorensen was forced out in 1944. Ford's

incompetence led to discussions in Washington about how to

restore the company, whether by wartime government fiat or by

instigating some sort of coup among executives and directors.

Nothing happened until 1945, with bankruptcy a serious risk,

Edsel's widow led an ouster and installed her son,

Henry Ford II, as president; the young man fired Bennett and

took full control.

The Dearborn Independent -

Antisemitism

Ford in the early 1920s sponsored a weekly newspaper that

published (among many non-controversial articles) strongly anti-semitic

views. At the same time Ford had a reputation as one of the few

major corporations actively hiring black workers; he was not

accused of discrimination against Jewish workers or suppliers. Ford in the early 1920s sponsored a weekly newspaper that

published (among many non-controversial articles) strongly anti-semitic

views. At the same time Ford had a reputation as one of the few

major corporations actively hiring black workers; he was not

accused of discrimination against Jewish workers or suppliers.

In 1918, Ford's closest aide and private secretary,

Ernest G. Liebold, purchased an obscure weekly newspaper for

Ford,

The Dearborn Independent. The Independent ran for

eight years, from 1920 until 1927, during which Liebold was

editor. Every Ford franchise nation-wide had to carry the paper

and distribute it to its customers.

The newspaper published

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was

discredited by

The Times of London as a forgery during the

Independent's publishing run. The

American Jewish Historical Society described the ideas

presented in the magazine as "anti-immigrant,

anti-labor, anti-liquor, and

anti-Semitic." In February 1921, the

New York World published an interview with Ford, in

which he said: "The only statement I care to make about the

Protocols is that they fit in with what is going on." During

this period, Ford emerged as "a respected spokesman for

right-wing extremism and religious prejudice," reaching around

700,000 readers through his newspaper. The 2010 documentary film

Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story (written by

Pulitzer Prize winner

Ira Berkow) noted that Ford wrote on May 22, 1920: ?If fans

wish to know the trouble with American baseball they have it in

three words?too much Jew.?

In Germany, Ford's anti-Jewish articles from The Dearborn

Independent were issued in four volumes, cumulatively titled

The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem

published by

Theodor Fritsch, founder of several anti-semitic parties and

a member of the Reichstag. In a letter from 1924,

Heinrich Himmler described Ford as "one of our most

valuable, important, and witty fighters." Ford is the only

American mentioned in

Mein Kampf. Speaking in 1931 to a Detroit News reporter,

Hitler said he regarded Ford as his "inspiration", explaining

his reason for keeping Ford's life-size portrait next to his

desk.

Steven Watts wrote that Hitler "revered" Ford, proclaiming

that "I shall do my best to put his theories into practice in

Germany," and modeling the

Volkswagen, the people's car, on the model T.

On February 1, 1924, Ford received

Kurt Ludecke, a representative of Hitler, at his home.

Ludecke was introduced to Ford by

Siegfried Wagner (son of the famous composer

Richard Wagner) and his wife

Winifred, both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke

asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause, but was

apparently refused. On February 1, 1924, Ford received

Kurt Ludecke, a representative of Hitler, at his home.

Ludecke was introduced to Ford by

Siegfried Wagner (son of the famous composer

Richard Wagner) and his wife

Winifred, both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke

asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause, but was

apparently refused.

While Ford's articles were denounced by the

Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the articles explicitly

condemned

pogroms and violence against Jews (Volume 4, Chapter 80),

but blamed the Jews for provoking incidents of mass violence.

None of this work was written by Ford, but he allowed his name

to be used as author. According to trial testimony, he wrote

almost nothing. Friends and business associates have said they

warned Ford about the contents of the Independent and

that he probably never read the articles. (He claimed he only

read the headlines.) But, court testimony in a

libel suit, brought by one of the targets of the newspaper,

alleged that Ford did know about the contents of the

Independent in advance of publication.

A libel lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish

farm cooperative organizer

Aaron Sapiro in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to

close the Independent in December 1927. News reports at

the time quoted him as saying he was shocked by the content and

unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's

"Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to

do with the editorials even though they were under his byline.

Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the

content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval.

Investigative journalist

Max Wallace noted that "whatever credibility this absurd

claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a

former Dearborn Independent employee, swore under oath

that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro."

Michael Barkun observed,

That Cameron would have continued to publish such

controversial material without Ford's explicit instructions

seemed unthinkable to those who knew both men. Mrs. Stanley

Ruddiman, a Ford family intimate, remarked that 'I don't

think Mr. Cameron ever wrote anything for publication

without Mr. Ford's approval.'

According to Spencer Blakeslee,

The ADL mobilized prominent Jews and non-Jews to publicly

oppose Ford's message. They formed a coalition of Jewish

groups for the same purpose and raised constant objections

in the Detroit press. Before leaving his presidency early in

1921, Woodrow Wilson joined other leading Americans in a

statement that rebuked Ford and others for their antisemitic

campaign. A boycott against Ford products by Jews and

liberal Christians also had an impact, and Ford shut down

the paper in 1927, recanting his views in a public letter to

Sigmund Livingston, ADL.

Ford's 1927 apology was well received. "Four-Fifths of the

hundreds of letters addressed to Ford in July 1927 were from

Jews, and almost without exception they praised the

Industrialist." In January 1937, a Ford statement to the

Detroit Jewish Chronicle disavowed "any connection

whatsoever with the publication in Germany of a book known as

the International Jew."

In July 1938, prior to the outbreak of war, the German consul

at

Cleveland gave Ford, on his 75th birthday, the award of the

Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal Nazi

Germany could bestow on a foreigner. James D. Mooney,

vice-president of overseas operations for

General Motors, received a similar medal, the Merit Cross of

the German Eagle, First Class.

Distribution of International Jew was halted in 1942

through legal action by Ford, despite complications from a lack

of copyright. It is still banned in Germany. Extremist groups

often recycle the material; it still appears on

antisemitic and

neo-Nazi websites.

One Jewish public figure who was said to have been friendly

with Ford was Detroit Judge

Harry Keidan. When asked about this connection, Ford replied

that Keidan was only half-Jewish. A close collaborator of Ford

during World War II reported that Ford, at the time over 80

years old, was shown a movie of the

Nazi concentration camps and was ill stricken by the

atrocities.

The damage, however, had been done. Testifying at

Nuremberg, convicted

Hitler Youth leader

Baldur von Schirach who, in his role as military governor of

Vienna deported 65,000 Jews to camps in Poland, stated,

The decisive anti-Semitic book I was reading and the book

that influenced my comrades was [...] that book by Henry

Ford, "The International Jew." I read it and became

anti-Semitic. The book made a great influence on myself and

my friends because we saw in Henry Ford the representative

of success and also the representative of a progressive

social policy.

International business

Ford's philosophy was one of economic independence for the

United States. His River Rouge Plant became the world's largest

industrial complex, pursuing

vertical integration to such an extent that it could produce

its own steel. Ford's goal was to produce a vehicle from scratch

without reliance on foreign trade. He believed in the global

expansion of his company. He believed that international trade

and cooperation led to international peace, and he used the

assembly line process and production of the Model T to

demonstrate it.

He opened Ford assembly plants in Britain and Canada in 1911,

and soon became the biggest automotive producer in those

countries. In 1912, Ford cooperated with

Giovanni Agnelli of

Fiat

to launch the first Italian automotive assembly plants. The

first plants in Germany were built in the 1920s with the

encouragement of

Herbert Hoover and the Commerce Department, which agreed

with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to

world peace. In the 1920s, Ford also opened plants in Australia,

India, and France, and by 1929, he had successful dealerships on

six continents. Ford experimented with a commercial rubber

plantation in the

Amazon jungle called

Fordl?ndia; it was one of his few failures. In 1929, Ford

accepted

Joseph Stalin's invitation to build a model plant (NNAZ,

today GAZ)

at Gorky, a city now known under its historical name

Nizhny Novgorod. He sent American engineers and technicians

to the Soviet Union to help set it up, including future labor

leader

Walter Reuther.

The Ford Motor Company had the policy of doing business in

any nation where the United States had diplomatic relations. It

set up numerous subsidiaries that sold cars and trucks and

sometimes assembled them:

- Ford of Australia

-

Ford of Britain

- Ford of Argentina

- Ford of Brazil

- Ford of Canada

- Ford of Europe

- Ford India

- Ford South Africa

- Ford Mexico

- Ford Philippines

By 1932, Ford was manufacturing one third of all the world?s

automobiles. Ford's image transfixed Europeans, especially the

Germans, arousing the "fear of some, the infatuation of others,

and the fascination among all". Germans who discussed "Fordism"

often believed that it represented something quintessentially

American. They saw the size, tempo, standardization, and

philosophy of production demonstrated at the Ford Works as a

national service?an "American thing" that represented the

culture of United States. Both supporters and critics

insisted that Fordism epitomized American capitalist

development, and that the auto industry was the key to

understanding economic and social relations in the United

States. As one German explained, "Automobiles have so completely

changed the American's mode of life that today one can hardly

imagine being without a car. It is difficult to remember what

life was like before Mr. Ford began preaching his doctrine of

salvation". For many Germans, Ford embodied the essence of

successful Americanism.

In My Life and Work, Ford predicted that if greed,

racism, and short-sightedness could be overcome, then economic

and technological development throughout the world would

progress to the point that international trade would no longer

be based on (what today would be called) colonial or

neocolonial models and would truly benefit all peoples. His

ideas in this passage were vague, but they were idealistic.

Racing

Ford maintained an interest in auto racing from 1901 to 1913

and began his involvement in the sport as both a builder and a

driver, later turning the wheel over to hired drivers. He

entered stripped-down

Model Ts in races, finishing first (although later

disqualified) in an "ocean-to-ocean" (across the United States)

race in 1909, and setting a one-mile (1.6 km) oval speed record

at Detroit Fairgrounds in 1911 with driver Frank Kulick. In

1913, Ford attempted to enter a reworked Model T in the

Indianapolis 500 but was told rules required the addition of

another 1,000 pounds (450 kg) to the car before it could

qualify. Ford dropped out of the race and soon thereafter

dropped out of racing permanently, citing dissatisfaction with

the sport's rules, demands on his time by the booming production

of the Model Ts, and his low opinion of racing as a worthwhile

activity. Ford maintained an interest in auto racing from 1901 to 1913

and began his involvement in the sport as both a builder and a

driver, later turning the wheel over to hired drivers. He

entered stripped-down

Model Ts in races, finishing first (although later

disqualified) in an "ocean-to-ocean" (across the United States)

race in 1909, and setting a one-mile (1.6 km) oval speed record

at Detroit Fairgrounds in 1911 with driver Frank Kulick. In

1913, Ford attempted to enter a reworked Model T in the

Indianapolis 500 but was told rules required the addition of

another 1,000 pounds (450 kg) to the car before it could

qualify. Ford dropped out of the race and soon thereafter

dropped out of racing permanently, citing dissatisfaction with

the sport's rules, demands on his time by the booming production

of the Model Ts, and his low opinion of racing as a worthwhile

activity.

Berna Eli "Barney" Oldfield (June 3, 1878

? October 4, 1946) was an American automobile racer and pioneer.

He was the first man to drive a car at 60 miles per hour (96

km/h) on an oval.[1] His accomplishments led to the expression

"Who do you think you are? Barney Oldfield?". Oldfield was lent

a gasoline-powered bicycle to race at Salt Lake City, which led

to a meeting with Henry Ford. Ford had readied two automobiles

for racing, and he asked Oldfield if he would like to test one

at Ford's Grosse Pointe track. Oldfield agreed and traveled to

Michigan for the trial, but neither car would start. In spite of

the fact that Oldfield had still never driven an automobile, he

and fellow racing cyclist Tom Cooper purchased both test

vehicles when Ford offered to sell them for $800. One of those

first vehicles was the famous "No. 999" which debuted in

October, 1902 at the Manufacturer's Challenge Cup. The car can

be found today at the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village.

In My Life and Work Ford speaks (briefly) of racing in

a rather dismissive tone, as something that is not at all a good

measure of automobiles in general. He describes himself as

someone who raced only because in the 1890s through 1910s, one

had to race because prevailing ignorance held that racing was

the way to prove the worth of an automobile. Ford did not agree.

But he was determined that as long as this was the definition of

success (flawed though the definition was), then his cars would

be the best that there were at racing. Throughout the book, he

continually returns to ideals such as transportation, production

efficiency, affordability, reliability, fuel efficiency,

economic prosperity, and the automation of drudgery in farming

and industry, but rarely mentions, and rather belittles, the

idea of merely going fast from point A to point B.

Nevertheless, Ford did make quite an impact on auto racing

during his racing years, and he was inducted into the

Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 1996.

Later

career

When Edsel, president of Ford Motor Company, died of cancer

in May 1943, the elderly and ailing Henry Ford decided to assume

the presidency. By this point in his life, he had had several

cardiovascular events (variously cited as heart attack or

stroke) and was mentally inconsistent, suspicious, and generally

no longer fit for such a job.

Most of the directors did not want to see him as president.

But for the previous 20 years, though he had long been without

any official executive title, he had always had de facto

control over the company; the board and the management had never

seriously defied him, and this moment was not different. The

directors elected him, and he served until the end of the war.

During this period the company began to decline, losing more

than $10 million a month ($134,310,000 a month today). The

administration of President

Franklin Roosevelt had been considering a government

takeover of the company in order to ensure continued war

production, but the idea never progressed.

Death

In ill health, Ford ceded the presidency to his grandson

Henry Ford II in September 1945 and went into retirement. He

died in 1947 of a

cerebral hemorrhage at age 83 in

Fair Lane, his Dearborn estate. A public viewing was held at

Greenfield Village where up to 5,000 people per hour filed past

the casket. Funeral services were held in Detroit's

Cathedral Church of St. Paul and he was buried in the Ford

Cemetery in Detroit.

Interesting Facts

Interest in materials science and engineering

Henry Ford long had an interest in

materials science and engineering. He enthusiastically

described his company's adoption of vanadium steel alloys and

subsequent metallurgic R&D work.

Ford long had an interest in plastics developed from

agricultural products, especially

soybeans. He cultivated a relationship with

George Washington Carver for this purpose. Soybean-based

plastics were used in Ford automobiles throughout the 1930s in

plastic parts such as car horns, in paint, etc. This project

culminated in 1942, when Ford

patented an automobile made almost entirely of plastic,

attached to a tubular welded frame. It weighed 30% less than a

steel car and was said to be able to withstand blows ten times

greater than could steel. Furthermore, it ran on grain alcohol (ethanol)

instead of gasoline. The design never caught on.

Ford was interested in

engineered woods ("Better wood can be made than is grown")

(at this time plywood and particle board were little more than

experimental ideas);

corn as a fuel source, via both corn oil and ethanol; and

the potential uses of cotton. Ford was instrumental in

developing charcoal

briquets, under the brand name "Kingsford".

His brother in law,

E.G. Kingsford, used wood scraps from the Ford factory to

make the briquets.

Ford was a

prolific inventor and was awarded 161 U.S. patents.

Georgia residence and community

Ford maintained a vacation residence (known as the "Ford

Plantation") in

Richmond Hill, Georgia. He contributed substantially to the

community, building a chapel and schoolhouse and employing

numerous local residents.

Preserving

Americana

Ford had an interest in "Americana".

In the 1920s, Ford began work to turn

Sudbury, Massachusetts, into a themed historical village. He

moved the schoolhouse supposedly referred to in the nursery

rhyme, "Mary

had a little lamb", from

Sterling, Massachusetts, and purchased the historic

Wayside Inn. This plan never saw fruition. Ford repeated the

concept of collecting historic structures with the creation of

Greenfield Village in

Dearborn, Michigan. It may have inspired the creation of

Old Sturbridge Village as well. About the same time, he

began collecting materials for his museum, which had a theme of

practical technology. It was opened in 1929 as the Edison

Institute. Although greatly modernized, the museum continues

today.

On the idea that he invented the automobile

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile, as is occasionally

believed. Indeed, he began as a race driver of other people's

cars. As Ford himself noted, by the 1870s, the notion of a

"horseless carriage was a common idea". Many people worked

toward the idea, as the history

of steam road vehicles and

of automobiles shows. Ford was, however, more influential

than any other single person in changing the paradigm of the

automobile from a very expensive, heavy, hand-built toy for rich

people into a lightweight, reliable, affordable, mass-produced

mode of transportation for working-class people.

On the idea that he invented the assembly line

Both Ford and

Ransom E. Olds are sometimes credited with the invention of

the

assembly line, although (as is the case with many

inventions) the assembly line's development included many

inventors. It combined the idea of

interchangeable parts (another gradual technological

development that is often mistakenly attributed to one

individual or another). After 5 years of empirical development,

Ford's first moving assembly line (employing conveyor belts)

began mass production on or around April 1, 1913. The concept

was first applied to subassemblies, and shortly after to the

entire chassis. Although it is inaccurate to say that Ford

personally invented the assembly line, his sponsorship of its

development and use was central to its explosive success in the

20th century.

Miscellaneous

Ford was the winner of the award of

Car Entrepreneur of the Century in 1999.

Ford published a book, circulated to youth in 1914, called

"The Case Against the Little White Slaver" which documented many

dangers of cigarette smoking attested to by many researchers and

luminaries.

Ford dressed up as

Santa Claus and gave sleigh rides to children at Christmas

time on his estate.

A compendium of short biographies of famous

Freemasons, published by a Freemason lodge, lists Ford as a

member.

Ford was especially fond of

Thomas Edison, and on Edison's deathbed, he demanded

Edison's son catch his final breath in a test tube. The test

tube can still be found today in

Henry Ford Museum.

In 1923, Ford's pastor, and head of his sociology department,

Episcopal minister Samuel S. Marquis, claimed that Ford

believed, or "once believed" in

reincarnation. Though it is unclear whether or how long Ford

kept such a belief, the

San Francisco Examiner from August 26, 1928, published a

quote which described Ford's beliefs:

I adopted the theory of Reincarnation when I was twenty

six. Religion offered nothing to the point. Even work could

not give me complete satisfaction. Work is futile if we

cannot utilise the experience we collect in one life in the

next. When I discovered Reincarnation it was as if I had

found a universal plan I realised that there was a chance to

work out my ideas. Time was no longer limited. I was no

longer a slave to the hands of the clock. Genius is

experience. Some seem to think that it is a gift or talent,

but it is the fruit of long experience in many lives. Some

are older souls than others, and so they know more. The

discovery of Reincarnation put my mind at ease. If you

preserve a record of this conversation, write it so that it

puts men?s minds at ease. I would like to communicate to

others the calmness that the long view of life gives to us.

Related Article:

Henry Ford - This is Your Life |