|

One of the most persistent myths in

automotive history is the belief that Henry

Ford invented the automobile. This, however,

is far from the truth. The automobile was

already in existence long before Ford

entered the scene. What he did

revolutionize, however, was the way

automobiles were manufactured. His

groundbreaking innovation was the

introduction of the moving assembly line - a

method that would forever change the

landscape of industrial production.

Before Ford's innovation, cars were

assembled one at a time, often by skilled

craftsmen who painstakingly put together

each component by hand. This process was

slow, expensive, and inefficient, making

automobiles a luxury item available only to

the wealthy. Ford recognized the need for a

better way - a system that would allow for

mass production at lower costs while

maintaining quality. His solution came in

the form of the moving assembly line.

The key feature of this revolutionary system

was the conveyor belt, a mechanism that had

already been used in other industries,

including meatpacking plants. The idea was

simple yet transformative: instead of

workers moving from one station to another

to complete various tasks, the product

itself would move along a track, stopping at

different stations where specialized workers

would complete specific tasks. This approach

maximized efficiency and minimized wasted

effort, allowing for a dramatic increase in

production speed.

|

|

After extensive experimentation and

refinement, Henry Ford and his team at the

Ford Motor Company successfully implemented

the moving assembly line in 1913 at the

Highland Park assembly plant. At first, the

vehicles were physically pulled down the

line by a rope, but soon, a simple chain

mechanism took over. This seemingly small

change had an enormous impact: the time

required to build a Model T dropped from

over 12 hours to just 90 minutes. This

breakthrough meant more cars could be

produced at a lower cost, bringing

automobile ownership within reach of the

average American.

However, not everyone welcomed this new

system. While the efficiency of the assembly

line was undeniable, it introduced new

challenges for workers. Previously,

employees had been involved in multiple

aspects of a carís assembly, which provided

a sense of craftsmanship and accomplishment.

With the moving assembly line, however,

workers were now assigned to perform a

single repetitive task, over and over again.

The work became monotonous, and strict

timing meant that employees had to complete

their tasks quickly before the car moved to

the next station. This led to increased

stress, mistakes, and dissatisfaction among

workers. Some employees found the work

unbearable and began leaving for jobs

elsewhere.

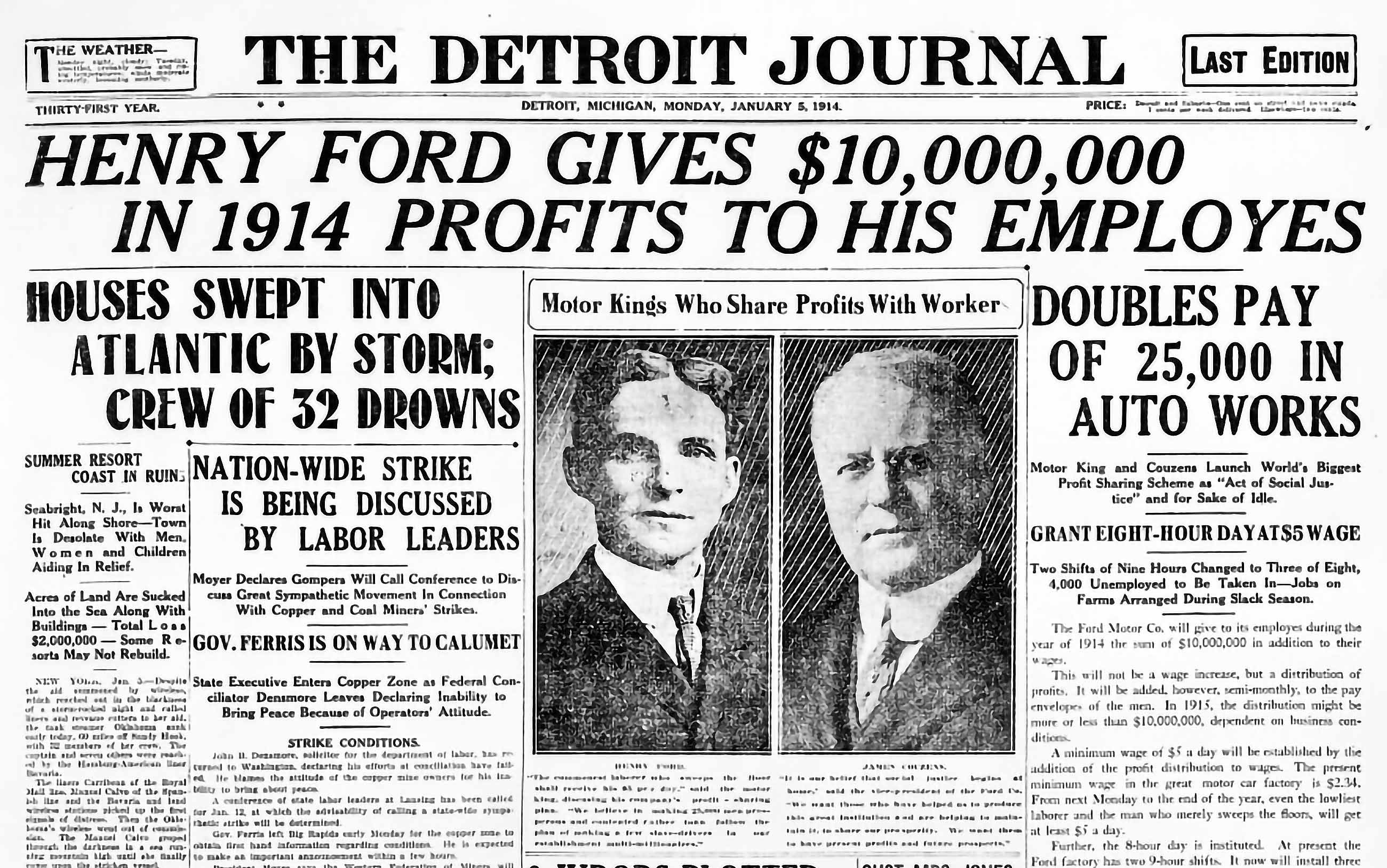

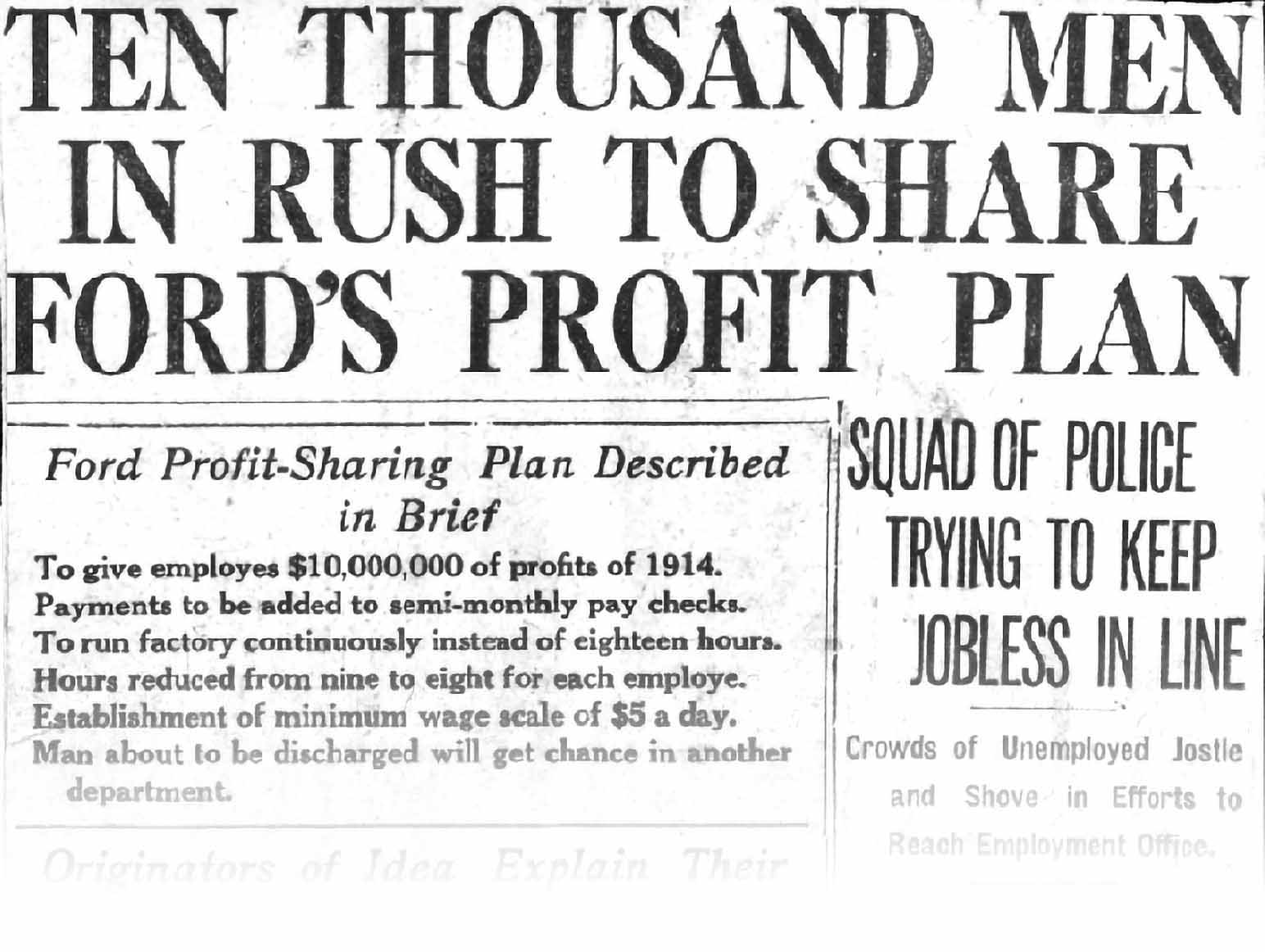

Recognizing this growing problem, Henry Ford

made a bold and unprecedented move - he

introduced the $5 workday in 1914. This

initiative more than doubled the daily wage

of his workers, from around $2.34 to $5. At

the time, many critics predicted that this

decision would drive the company into

financial ruin. Instead, it had the opposite

effect.

Word of Fordís high wages spread

across the country, and workers flocked to

Detroit in hopes of securing a job at the

Ford Motor Company. The company was suddenly

inundated with skilled and dedicated workers

who were willing to tolerate the monotonous

assembly line in exchange for better pay and

improved living standards.

But Ford didnít stop at increasing wages. He

also reduced the length of the workday.

Shifts were cut from nine hours to eight,

which not only made the work more bearable

but also allowed for the creation of a third

shift, turning Fordís factories into

round-the-clock operations. This further

boosted production capacity and

profitability, setting a precedent for the

modern five-day workweek and influencing

labor policies across industries.

This new approach to manufacturing and labor

became known as "Fordism," a term that came

to symbolize the combination of mass

production and higher wages. Other

industries soon followed Fordís example,

adopting similar methods to increase

efficiency and attract a stable workforce.

The ripple effects of Fordism extended

beyond manufacturing, influencing economic

and social structures throughout the 20th

century.

One of the most significant outcomes of

Fordís moving assembly line was the dramatic

reduction in the price of the Model T. When

it was first introduced in 1908, the Model T

sold for $825 - a hefty sum at the time. By

1925, thanks to increased efficiency in

production, the price had dropped to just

$260. This made the automobile more

accessible than ever before, transforming it

from a luxury item into a household

necessity for middle-class Americans. Not

only could more families afford to buy a

car, but Fordís own employees - who had once

been unable to purchase the products they

built - could now afford to drive the very

vehicles they assembled.

In the end, Henry Ford didnít invent the

automobile, but his contributions to

manufacturing reshaped the industry and

changed the world. His pioneering use of the

moving assembly line made cars affordable

for the masses, revolutionized industrial

production, and set new standards for wages

and working conditions. Today, his

innovations remain the foundation of modern

manufacturing, proving that sometimes, the

greatest revolutions come not from

invention, but from reinvention.

|